Over one hundred years ago, automobile manufacturers invented dealers to save themselves the capital cost of maintaining inventory and to make the process of delivering new automobiles to customers both efficient and someone else’s problem. “Those that do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” The quote, commonly attributed to Santayana, describes Tesla today: Tesla needs dealers to make a profit. It has none. That is one of the reasons it is currently losing money – almost a quarter of a billion dollars in just the first three months of 2019.

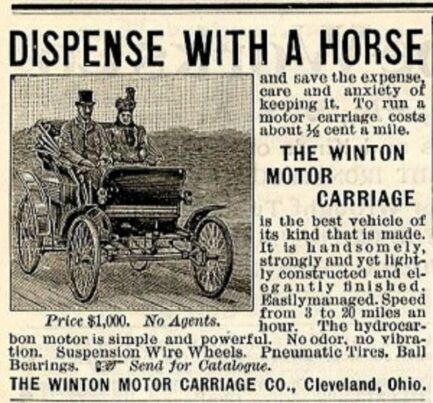

In the first years of the twentieth century, automobile manufacturers seldom has access to bank loans. For the most part, they relied upon investors to raise money, an arrangement that was fine for starting the enterprise, but not an adequate source of working capital to keep it going. (Even Henry Ford, as noted in our previous post about Ford and the Dodge brothers.) As the industry grew, automobile manufacturers were no longer competing with the horse. They were now competing with each other.

Technology – both in the automobile itself and in the methods of production – was advancing with remarkable speed. In 1904, the Oldsmobile’s one-cylinder runabout was the best-selling automobile in the United States, with 5,508 sold. Twelve years later, Packard introduced its famous “Twin Six,” a luxury priced automobile featuring a V-12 engine. It sold 10,645 of them. The best-selling car in 1916, of course, was the Model T – with 734,811 rolling off the assembly line.

For these reasons, early automobile manufacturers were almost universally undercapitalized.

When we refer to early manufacturers as “under-capitalized,” the common image is of a shoestring operation struggling to build a few cars and failing when it could not sell them. But that is not the real picture of “under-capitalized” automobile manufacturers in the early days. They were successful – very successful.

That was the problem.

The automobile market in the first two decades of the twentieth century was expanding so rapidly that automobile manufacturers required huge levels of investment to be and remain competitive. In 1904, William C. Durant capitalized Buick at $100,000.00 and displayed the Buick roadster at the New York Auto Show. He booked 1,108 orders. By 1907, Buick production had reached four times that number and Durant was envisioning a merger of automobile companies, to be the United Motors Corporation. To capitalize it, he intended to issue stock totaling $1.5 million. He approached J. P. Morgan & Company to underwrite one-third of the issue. J. P. Morgan himself rejected the idea. He could not see the automobile as anything but a rich man’s toy and called Durant an “unstable visionary.”

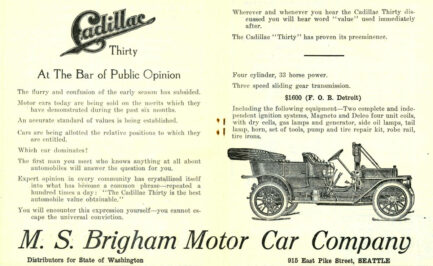

By 1909, Durant had founded General Motors. To Buick, he had added Oldsmobile, Oakland, and Cadillac. Durant now wanted to buy Ford – and Ford had just lost the first round of the Selden patent litigation, so might be amenable to the right offer. To make that offer, Durant approached a bank to borrow $2 million, toward raising $8 million for the purchase. The bank turned him down.

The automobile industry, however, continued to expand – and expand, and expand. But when banks finally did begin loaning to the industry, they were quick to cut off funds at the slightest setback.

In 1910, a correction in the stock market triggered banks cutting off credit to automakers, including General Motors. With its working capital cut off by banks calling loans and seizing accounts to offset loan balances, General Motors was forced to shut down production – a loss Durant calculated at $60,000 a day to a company that had fixed plant and equipment worth $14 million and $26 million of inventory. Durant went on a rapid cross-country quest, borrowing from General Motors dealers and the banks with whom those dealers did business, thereby raising the money needed to keep operating.

Tesla’s troubles today are really the same problems facing the automobile industry over one hundred years ago. But Tesla is ignoring the solution devised by the industry so long ago and used successfully ever since.

Financing unsold inventory was an enormous problem for early automobile manufacturers. Unsold inventory tied up money they desperately needed for financing plant and equipment and meeting payroll. The more production increased, the bigger the drag from unsold inventory. This financial drain was exacerbated by disorganized distribution that prolonged the time between production and sale.

There were, however, people who had access to the capital that the automobile manufacturers lacked. These were local businessmen already successful within their communities. They had existing business relationships with local banks. They could borrow money to finance an inventory of new automobiles awaiting sale to the ultimate purchaser. They became the first automobile dealers.

With the dealer able to finance new car inventory, the automobile manufacturer was able to sell its production to the dealer at the factory door. The dealer and his bank paid cash to the manufacturer. The car was sold to the dealer “F.O.B. Detroit.” “FOB” meant “free on board,” a phrase denoting that the seller has completed its end of the transaction and that any risk of loss thereafter is upon the purchaser, i.e., the dealer. It was up to the dealer to get the car to the showroom floor and sell it to the consumer.

Two problems solved: the manufacturer shifted the burden of financing unsold inventory to the dealer and shifted the problem of distribution to the dealer.

But not Tesla.

When Tesla builds an automobile and ships it, Tesla still owns it. While that vehicle is in transit, Tesla still owns it. Tesla owns it until the customer pays for it, buying it directly from Tesla. Tesla must support the entire cost of the entire inventory of vehicles not yet sold to the ultimate purchaser.

In the meantime, Tesla is not making a dime from that unsold inventory. It can’t use the money tied up in that inventory to build more Tesla’s or develop future models.

This is why Tesla needs dealers to make a profit.

There is, however, yet another reason Tesla needs dealers to make a profit.

By 1919, the automobile industry had become the largest new industry in the United States. Automobile manufacturers no longer had problems raising working capital. It was now the dealers who needed access to better financing. To meet expanding demand, manufacturers needed more dealers and dealers needed ever larger inventories. The ability of dealers to finance this inventory directly affected the ability of the manufacturers to meet demand.

That year, General Motors invented a way to assure dealers would have access to the financing needed for adequate inventory and, at the same time, earn a handsome profit to General Motors.

It formed the General Motors Acceptance Corporation, or “GMAC.” GMAC later became best known for consumer financing (and, through various corporate crises, became today’s Ally Bank). However, GMAC originally was organized to provide inventory financing to General Motors dealers. By 1919, General Motors size allowed it to offer credit to dealers in competition with local banks or when local banks were not an adequate source of financing. General Motors still was paid cash at the dock for the automobile and the dealer still bore all the costs of distribution. All that had changed was that General Motors, rather than outside banks, profited from the dealer’s expense of financing the unsold inventory.

This model was so successful that other automobile manufacturers copied GMAC to create their own captive financing arms. Today, all major automobile manufacturers offer this “floor plan” financing for dealership inventory.

Except Tesla. Tesla has no way to make money financing unsold inventory because Tesla has no dealers.

Tesla reported a $702 million loss for the first quarter of 2019. Though it originally had projected profits for the first and second quarters, Tesla now expects no profit until the third quarter. Tesla explains that production will “be significantly higher” than deliveries this year. That means Tesla will be supporting a large inventory of unsold automobiles.

It is an expense they cannot afford and could have avoided – if they sold Tesla’s through dealers.

Tesla attributes some of the loss to logistic problems delivering vehicles in Europe and China. But the problem of exporting and importing automobiles is not qualitatively different than distributing automobiles within the United States. Following World War Two, automobile manufacturers in Europe began exporting automobiles to the United States. But they did it through importers, such as the legendary Max Hoffman (who introduced Volkswagen and BMW, as well as Mercedes-Benz, to the post-War market in the United States). These importers took on the role of an importing dealer, paying at the factory gate for the vehicles and supporting the inventory of vehicles and parts necessary to sell and service them.

Though largely ignored in the press, within Tesla’s first quarter results is yet another reason that Tesla needs dealers to make a profit. As noted by stock market analyst Jim Cramer, Tesla reported a $57 million loss before adjustment for depreciation, interest, taxes, and amortization (EBDITA) in the first quarter of 2019. That means Tesla is losing money on every car they build.

After initially announcing the $35,000.00 Model 3, Tesla quickly retreated from selling them online (where 78% of Model 3 models are sold). The $35,000.00 Model 3 promised for years and finally offered for sale on February 28th was pulled from online sale on April 11th. It now can be ordered only in a Tesla store or by phone.

Anyone who has ever bought an automobile or truck from a dealer knows why Tesla did that.

You don’t really want to sell your loss leader and you can’t up-sell a customer online.

Which may be the most important reason why Tesla needs dealers to make a profit.

For other posts about how history repeats itself with Tesla, see our other post about Tesla and Ford and our post about its CEO, Elon Musk, and the Securities and Exchange Commisssion.