Automobile Chronicles is about “Automotive History – Then and Now.” But there would not be any automotive history were it not for the wheel. Two of our readers, Emily and Melissa, who are both students and students of history, recently pointed this out and directed our attention to an article discussing the history of the wheel they had discovered in their research.

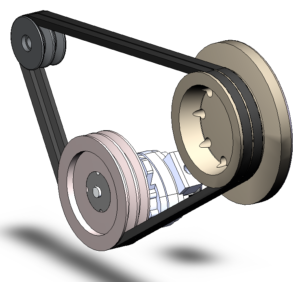

They have a point. Automotive history tends to focus on more glamorous subjects – the artistry of the automotive form as it has evolved over the decades, the increases in power and performance as engineering overcomes limits once thought impossible to surmount. But, none of that would go anywhere – literally – without the wheel. Indeed, if there is any form fundamental to the automobile, it must be the perfectly circular wheel. Not only does the automobile use the wheel to move and steer, it is wheels in the form of pulleys that harness engine power to operate accessory drives essential to operating its electrical, cooling, and emissions systems and providing climate comfort for its occupants.

So, who invented the wheel?

That distinction is lost to history, though scholars date the first use of the wheel – as a potter’s wheel – to Mesopotamia in 3500 B.C. Using wheels for transportation developed much later – probably because the wheel requires an axle to be of any real use – and combining the wheel and an axle is a rather sophisticated mechanical achievement, as explained by Interesting Engineering:

“The idea of adding an axle isn’t a simple one. For the system to work, the wheel must rotate freely around the axle. This is achieved by fitting the axle directly in the center of the wheel to maximize continuity during motion. In addition, the axle and the hole alignment must be perpendicular to reduce friction. Furthermore, the axle should remain as thin as possible to reduce its surface area while still being able to support the load.”

The wheel was a uniquely human invention – not something copied form nature. Egyptian and others may have used logs as rollers. But logs are not wheels. Wheels required human ingenuity to devise, and then to evolve from a tool used to produce pottery or make moving loads easier into the basis of transportation.

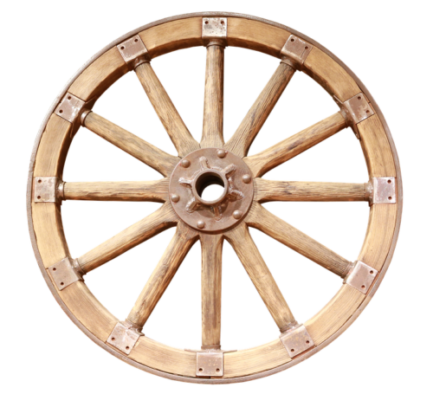

By the time of ancient Greece, about 2000 B.C., the wheel had spokes, an improvement attributed to the Shintashta culture that also developed the first known chariots. About one thousand years later, the Celts added iron rims to their wheel to increase wear – the first known effort in history toward increasing tire mileage.

But what about the pulley – the smaller wheel that is the foundation of those accessory drives and timing belts of today’s engines? That, too, dates to Mesopotamia, where pulleys were used for lifting water starting about 1500 B.C. The device’s modern popularity, however, dates to that uniquely American problem-solver, Benjamin Franklin.

The story, according to Ebudilla.com, is that Franklin, in 1730, ordered a new printing press. It was too large to fit the staircase leading to his third-floor premises. Seeing the wheels on the wagon that had delivered the press gave him an idea and he rigged up a pulley system to lift the press, by-passing the stairs. From there, the idea was copied and spread. So, at any rate, goes the story – and it’s a good story, even if there may have been some embellishment over the years.

We cannot end this post, though, without mentioning the men who made the wheel what it is today: John Boyd Dunlap, a veterinarian in Belfast, and John Fagan, the physician treating Dunlap’s son. Dr. Fagan had prescribed cycling as a cure for headaches afflicting the child. To cushion the bumps, they invented the pneumatic tire. Mr. Dunlap would create the tire company bearing his name. Dr. Fagan became Sir John Fagan when he was knighted.

On this Sunday, May 26th, many of us – certainly this author – will be glued to the television screen from early morning to late night as the annual “Greatest Day in Racing” progresses from the Grand Prix of Monaco through the Indianapolis 500 and ends with the Coca-Cola 600. The commentators will tell us about the aero packages, the engines (or “power units” as Formula One calls its hybrid motor). They will certainly tell us about the tires – the compounds, the wear, and the inevitable tire failures.

They probably won’t mention the wheel that made it all possible.

So thanks, Emily and Melissa. Every now and then, it is good to be reminded that today’s accomplishments and events are grounded in their history.

In that sense, automotive history begins long before the automobile.