The herd mentality is alive and well among automobile industry executives, not excluding Mary Barra and Jim Farley. Viewing Elon Musk and Tesla as their lodestar, automobile manufacturers seem intent on destroying the dealership model of sales. They’re going to regret that because they’re going to do what they always do – make too many cars and trucks.

A recent article in Car and Driver magazine about the future of automobile dealers touched upon this central point but did not really give it the emphasis it deserves.

The dealership model of automobile sales was developed as the answer to two problems: the undercapitalization of manufacturers and the seasonal variation in sales. Automobile manufacturers today may be so flush with cash that they can, for example, squander billions on driverless cars (as General Motors, Ford, and Volkswagen have done), but the second problem has not disappeared. It is only hiding.

The last few years have been lush times for automobile manufacturers because of scarcity. The pandemic, chip, and other supply chain issues (exacerbated, of course, by the industry’s earlier moves to “just-in-time” inventory systems that shifted parts inventory costs to suppliers but also forfeited direct control over that inventory) coupled with very low interest rates resulted in empty dealer lots, new cars routinely selling above “sticker,” and used cars that didn’t depreciate.

It won’t last. And when it flips, the automobile manufacturers are going to need their dealers, just as the industry has needed them throughout its history.

Globally, automakers have enormous excess production capacity. Excess production capacity is inevitable in an industry in which profit depends on the volume of sales. No manufacturer wants to so limit itself that it cannot meet demand, thereby ceding sales to competitors that have more capacity. Developing new models today is as necessary to being competitive as it has ever been. Amortizing development costs over a production run will always mean that a successful product makes huge profits and an unsuccessful one creates huge losses. It also means the incremental cost of producing one more vehicle will always encourage over production of laggard models.

Here is how that works. Assume development costs of a new model at $15 billion, which is actually a low number for an entirely new model. Assume also projected sales of 1.5 million vehicles over a product life of five years. To assure that the new model makes back enough money that the manufacturer can recoup its development costs and thereby finance the next new model, each vehicle sold must generate $1,000 in revenue above the direct and indirect costs of production (i.e., materials and labor, plant overhead, advertising costs, interest expenses, health care and pension costs, salaries, etc.).

Once the manufacturer has hit that projected sales target, that $1,000 is no longer needed to recoup costs and becomes the purest of all profit.

It leverages the other way, as well. If, for example, the new model is actually selling at a rate that’s likely to miss the target by 250,000 vehicles, then it will fail to recoup $250 million. Faced with that crisis, the manufacturer will make the rational move: it will drop the price. Even if dropping the price by $500 per vehicle means recouping less, the reality is that every vehicle sold for more than the basic costs of producing it – labor and materials – means the vehicle is producing an “operating profit” (revenue above direct costs of production) and the manufacturer is reducing its overall loss on the model. That same logic also means that a vehicle that has hit its production target can be sold for less and still generate a very large profit for the manufacturer, allowing it to progressively reduce the price and keep the vehicle in production.

There is another element of automobile production that bears on profit. Mass production requires constant production to fully achieve the economies of scale that allow predictable pricing. Once you have an assembly line in operation, shutting it down even briefly costs millions of dollars. (In 2009, a survey of automobile industry executives reported them as calculating the cost of shutting down an assembly line at $25,000 to $50,000 a minute. In 2008, Chrysler triggered a spat with one of its suppliers, forcing the supplier into bankruptcy and threatening the closure of fourteen assembly plants as a consequence. The company’s lawyers told the bankruptcy court that Chrysler could face $225 million in costs from a shutdown of those plants.) So, you do everything possible to avoid cutting production. You cannot match production to demand, day to day or even month to month. You do everything possible to keep the rate of production at the level projected when determining the amortization of that model over its expected production life.

Against these background economics, it is worthwhile to appreciate the current state of the automobile industry and its lock-step march toward an electric future. (There are many reasons to question whether the notion of an all-electric automotive future is feasible or desirable, and it is evident that automobile manufacturers are counting on governments to force adoption of electric automobiles. All of that is fair game for comment. But that is beyond the scope of this post, which is limited to the role of dealers in the industry’s future.)

Today, electric vehicles are less than five percent of the market for new automobiles and trucks. Overall, new cars and trucks remain a scarce commodity – in the sense that economists use the term ‘scarcity.’ Tesla has been able to operate without dealers because the market it was creating was far larger than its ability to meet the demands of that market, one in which it had no competition. It does not have to be a large overall market to accomplish this. It need only be a market that is much larger than production volume.

But success with any automobile or truck means that someone will compete. In the 1950’s, Volkswagen created a market for a small, inexpensive vehicle with low operating costs. American Motors and Studebaker booked profits by reworking existing models as “economy cars.” That led the major manufacturers in the 1960’s to aim new smaller cars at that market, redefining it, expanding it, and ultimately overwhelming it.

Eliminating dealers, or the functional equivalent – attempting to avoid the impact of state franchise protection laws by reducing their role to little more than delivery agents and eliminating their profitability – necessarily means that manufacturers must absorb the costs now incurred by dealers.

These are the costs of overproduction and industry overcapacity.

Volume automobile manufacturers want to sell as many vehicles as possible. To that end, they will develop new and improved models that are intended to increase sales and market share. Some of those new models will gain more favor with customers than others. The manufacturers of those others will respond by cutting the price of their laggard model, as they themselves introduce other new models that they hope will be winners. Industry economics, as illustrated above, mean that manufacturers will constantly seek to meet demand for popular models even as they simultaneously cut prices to move those that are less popular.

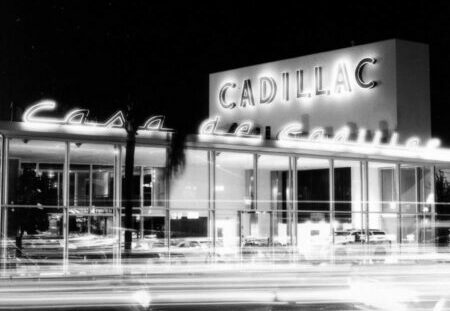

History, it is said, repeats. The period following World War Two through the 1950’s can tell us something about what the automobile industry is experiencing currently.

Following World War Two, demand for new cars meant anything would sell. Production resumed with face-lifted 1942 models as manufacturers raced to be first to the market with completely new models. As those new models became available, starting in 1948, demand continued to exceed supply as the population entered a decade of rapidly increasing prosperity. By 1952, that seller’s market had turned into a buyer’s market. Ford and General Motors began a price war in which other manufacturers were collateral damage. Both of those manufacturers also poured money into development of new, more advanced models, leading to record sales and profits in 1955. (In 1955, General Motors became the first corporation to make a profit of $1 billion in a year.)

When the post-War seller’s market turned into a buyer’s market, it was the automotive dealer that made it possible for the manufacturers to maintain production even as buyers became more selective and price sensitive. The dealers took the inventory and the costs associated with it. Any seasonal variations in demand were ironed out by putting seasonally excess production into dealer inventory. (The manufacturers had even figured out how to make money on that inventory by creating their own dealer finance divisions, such as General Motors Acceptance Corporation, to finance dealership inventory – a “floor plan,” in trade terminology). Collectively, dealerships also created the secondary market in used cars that supported the market for new cars. By having a large inventory of new vehicles, dealers were able to capitalize with instant gratification on the urge to have a new car. People became accustomed to budgeting a car payment as they would a mortgage or rent payment, which also made it possible for them to trade for a new car every two or three years – a concept that would eventually lead automobile dealers to invent leasing new cars.

As the experience of the post-War 1940’s and 1950’s illustrates, in the automobile industry scarcity will always lead to overproduction. Overproduction will always lead to price-cutting. Price-cutting, in turn, overall diminishes the value of existing vehicles as trade-ins, putting further pressure on new car prices and making introduction of new models just that much more essential to future profitability for the manufacturers.

Tesla may now be able to sell every vehicle it produces. General Motors and Ford may be able to book orders for electric pickup trucks into 2025. But it won’t last. In fact, the recent news that Tesla is doubling the discount on the Model Y and Model 3 to $7,500 tells you Tesla is putting money on the hood to move the product and maintain production volume – a problem directly related to not having dealers to smooth out variations in customer demand. See also our post Tesla Needs Dealers to Make a Profit.

Yet, some automobile manufacturers act as though it will last, and last forever.

General Motors is touting a new plan to cut costs. Instead of holding inventory on dealer lots, they’ll use sales data to manufacture cars that anticipate customers’ selection and hold them at distribution points located within a day of the dealer. Only there’s nothing new in that plan – it’s the same “pop coms” (for “popular combinations”) scheme the company used in the late 1990’s. (It also it deprives the company of the interest income it would derive from floor planning that inventory.) Ford intends to restrict dealers of its electric vehicles to a single demonstrator. That’s not too different from the immediate post-War years, when ordering a car was the expected way to buy. But that model rapidly disappeared as production came closer to demand and dealers were able to stock inventory. Ford may choose to deprive its dealers of inventory. But this is a competitive industry. When other manufacturers see that they’ve been handed an advantage by Ford, those other manufacturers will stock dealers with electric inventory and customers will have the choice of having a new vehicle now or one later. When that’s the choice, now typically wins.

Automobile dealers today are as essential to the financial health of automobile manufacturers as they were a century ago. The scarcity of new automobiles and trucks of the past two years was artificial. Some automobile manufacturers are building a new business model based on the belief that they can make scarcity permanent, dynamically balancing supply so that it is always just a little short of demand.

In the automobile business, it doesn’t work that way.

It never has.

It never will.