Reviled as the man who killed Kissel, Archibald Moulton Andrews also is blamed for the destroying Moon and Hupmobile in an ultimately futile quest to build his dream car, the Ruxton. Writing for Hemmings Classic Car and Hemmings.com, author Jim Richardson called Andrews “a song-and-dance man who fancied himself a carmaker,” but “knew nothing about building and selling automobiles” and “ran into the ground” the automobile manufacturers he controlled. The New York Times claimed in 2014 that Andrews died a fugitive in Canada and had been convicted of bribing a judge. In reality, it was the other way around. Three failing car companies killed the Ruxton.

The New York Times chose to tell a false tale. Apparently, the Times author did not read the paper’s own obituary reporting Andrews death in 1938 at his home in Greenwich, Connecticut. Andrews was never convicted of a crime, much less a fugitive. Richardson, like many others who accuse Andrews of bankrupting these companies, smugly ignores the actual history of these companies and the multiple management mistakes that fatally wounded each of them – mistakes made many years before Archie Andrews became involved with them.

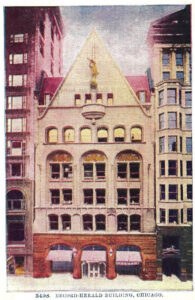

Andrews’ life was regarded by his contemporaries as a ‘rags to riches’ saga. Born in 1879, his first job was selling newspapers in front of the Herald building located in the “Loop” in downtown Chicago, Illinois. By the age of 21, Andrews was managing the “unlisted” stock department at a Chicago brokerage – “unlisted stocks” being those not traded on recognized exchanges and, thereby, the most speculative. A year later, Andrews had formed his own brokerage firm. By 1920, Andrews owned the Herald building, renaming it the Andrews building.

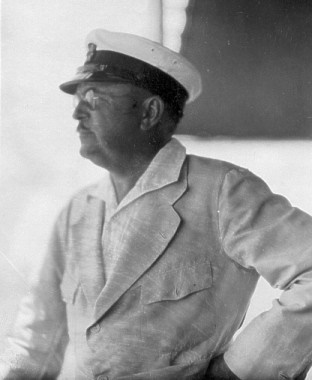

Andrews lived large. He was a celebrity as comfortably at home on his yacht as he was in the boardrooms of industry. In 1920, he purchased the 95-foot ketch-rigged sailing yacht Zahma, described by Rudder Magazine in December of that year as having “five staterooms . . . palatially furnished and a beautiful sea home.”

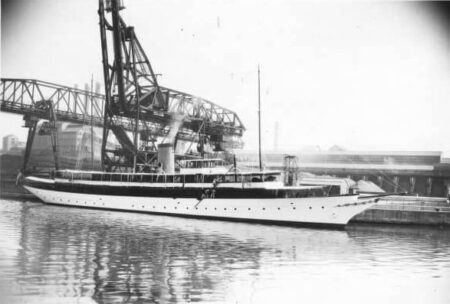

In June of 1929, Andrews bought the 222-foot yacht Sialia from Henry Ford. Requiring a crew of thirty-six, the press reported in 1932 that operating the Sialia cost Andrews over $137,000 annually. His eastern residence, “Freestone Castle” in Edgewater Park, Greenwich, Connecticut, purchased in 1929 for $300,000, was an ivy-covered mansion befitting a man of vast wealth. (More about Henry Ford can be found in previous posts.)

In later years, Andrew’s brokerage firm created an offering that permitted customers to purchase a bundle of one share each in twenty-five different companies – the forerunner of today’s mutual funds. The New York Stock Exchange promptly established rules prohibiting such bundled sales and Andrews, just as promptly, sued the stock exchange and won. His fortune, estimated at between $50 million and $80 million before the stock market “crash” of 1929, had been built on the promotion and sales of securities and real estate, with an emphasis on troubled companies. He claimed to have lost a fortune in the “crash” and made another afterward.

Andrews, however, was not a traditional businessman.

Today, we would instantly recognize Andrews as a “corporate raider,” “activist investor,” or “corporate takeover specialist.” These investors focus on buying stock of companies that are performing poorly and have depressed share prices that undervalue the company’s assets. With the leverage their shareholdings provide, they demand management changes, even corporate divestitures, to realize the true value of the underlying assets and increase the value of the stock.

Archie Andrews may not have invented the concept, but he built his fortune in exactly that manner. He then used that fortune to invest in companies that were very successful, becoming a respected businessman and member of the boards of directors of several large corporations.

One of those was the Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company.

Today, Budd is fondly recalled by railroad enthusiasts as the manufacturer of the streamlined stainless-steel passenger cars used by Burlington for their Zephyrs and by other rail lines, as well, in the 1950’s and 1960’s. However, in the 1920’s and 1930’s, Budd’s primary business was manufacturing automobile bodies. Its customers included Dodge, Willys-Overland, Studebaker, and Chrysler, among others. Budd’s primary competitors were the Briggs Manufacturing Company and Murray Corporation of America, both of whom had major contracts with Ford.

Murray also built the bodies for Hupmobiles manufactured by the Hupp Motor Car Company. In 1925, Murray had acquired Hupp’s in-house body building operation in Racine, Wisconsin as part of a five-year deal making Murray the exclusive manufacturer of Hupp bodies. However, transporting those bodies from Racine to Hupp’s assembly plant in Detroit eliminated any profit for Murray. It was obvious by 1928 that Murray’s contract with Hupp would not be renewed on similar terms.

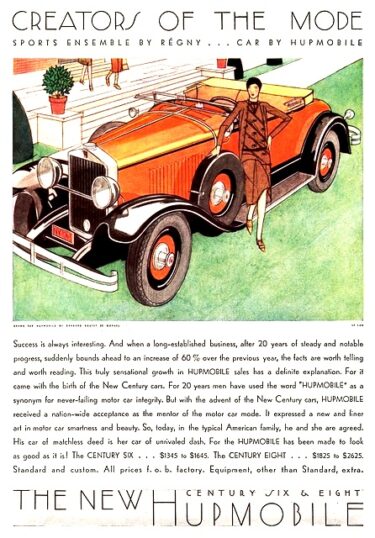

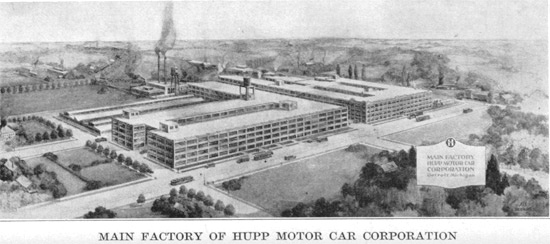

Hupp had been successful in the mid-1920’s, but its management had then made mistakes that caused lasting damage to the company. In 1925, Hupp introduced new eight-cylinder Hupmobiles and replaced its four-cylinder models with six-cylinder models. Then, in 1928, Hupp’s management expanded production capacity by acquiring Chandler-Cleveland Motors Corporation and its large Detroit assembly plant. Hupp’s production reached 65,881 automobiles in 1928.

But the next year was different. Even though the automobile industry was booming, Hupp’s production in 1929 dropped 23% to 50,578. Hupp’s more expensive models had priced many of its former customers out of the brand. Hupp’s efforts to build sales of its more expensive models backfired on its profits. Hupmobiles were offered in such variety that economies of scale could not be reached in production of them. The plant Hupp had acquired now turned out to be too large, saddling it with overhead costs it could not afford on the reduced volume. After the restyling of the 1928 models was no longer fresh, Hupmobile sales slid, with nothing on the horizon likely to alter the downward trajectory.

In 1928, Archie Andrews was also a member of the Board of Directors of Hupp Motor Company.

Budd, as did its competitors, employed in-house automotive designers and engineers. In addition to providing design assistance for customers lacking their own design departments, these staff designers and engineers created proposals for entirely new models. (John Tjarda, for example, designed the “Dream Car” while on Brigg’s staff that ultimately became the Lincoln Zephyr.) Usually, these designs were only on paper. But body manufacturers also built running prototypes to more effectively display and promote proposed designs.

In 1926, Budd began developing a front wheel drive prototype automobile.

In the mid-1920’s, front wheel drive was an exciting technology seriously considered for future production by several major automobile manufacturers. Front wheel drive had established itself in racing, where front wheel drive Millers dominated the Indianapolis 500. In 1925, Packard, the premier luxury automobile manufacturer of the time, signed a $5,000 per year contract with Harry Miller, designer of Indianapolis race cars, to consult on front wheel drive design for passenger cars. In 1931, with engineering assistance from Cornelius Van Ranst, one of Miller’s engineers, Packard produced a prototype front wheel drive sedan.

Packaging front wheel drive, however, created design challenges. Locating the transaxle ahead of a straight-eight engine added substantial length to the front of the automobile. Packard addressed that issue in its prototype by designing a new V-12 engine that was shorter than Packard’s existing in-line eight. However, Packard’s transaxle design was complex and the unit unreliable. Unwilling to accept the increasing costs of developing a transaxle that would meet their standards, Packard ended the front wheel drive project. (The project, however, resulted in one notable success: the V-12 engine designed for the front wheel drive prototype became the production engine in Packard’s most expensive automobiles, introduced as the new “Twin Six” in 1932. The Packard front wheel drive prototype survived and is one of the automobiles in the private Bahre Collection, located in Paris, Maine.)

Earlier, in 1927, the Auburn Automobile Company also began development of a front wheel drive automobile. It employed both Miller and Van Ranst, who ultimately was primarily responsible for the transaxle design employed in the Cord L29. However, the design did not overcome the packaging problem. The Cord’s transaxle was located ahead of its in-line eight-cylinder Lycoming engine, positioning the engine far back in the chassis. That, in turn, led to diminished weight over the driven front wheels, causing reduced traction on steep hills.

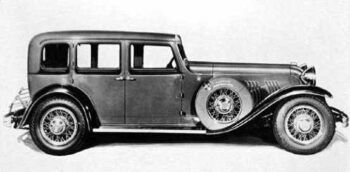

The Budd prototype was brilliant. Developed through the joint efforts of body designer Joseph Ledwinka and engineers William J. Muller and Earl J. Ragsdale, it was ten inches lower than an equivalent rear wheel drive automobile – so low that running boards were unnecessary and were omitted. The styling was striking, with a rakish forward slant to the roofline and a hood so low that was barely taller than the tops of the front fenders. (Ledwinka would later design the Citroen Traction Avant, for which Budd built the bodies. Ragsdale would later patent “shotwelding” stainless steel, making possible those Budd streamlined trains.)

Archie Andrews was quick to see the promise of the Budd prototype. Murray’s unprofitable contract with Hupp was ending and Hupp needed a new, stylish model with advanced engineering that would leapfrog its competition to stop its sliding sales. Hupp also had a national dealer network that could successfully promote the car. As a member of the boards of both Budd and Hupp, Andrews envisioned a perfect combination – one where Budd would build the bodies for the car to be manufactured and marketed by Hupp.

Andrews was undoubtedly correct.

He pitched this proposal to Hupp’s management.

As it would turn out, this to be Hupp’s last chance for survival as an automobile manufacturer.

Hupp’s management chose not to take that chance. In 1929, Hupp refused to build the Budd prototype.

We cannot know how Hupp’s future would have been affected, had its management accepted Andrews’ plan. Missed opportunities never display the missed outcome. But there is reason to believe Hupp could have been successful producing and marketing the Budd prototype as a Hupmobile. Introduced as a 1929 model in late 1928, despite the onset of the depression and adverse publicity resulting from its inherent traction deficiencies, 5,014 Cords were produced in slightly over two calendar years. Had Hupp entered the market with their own front-wheel drive model, the technology could have been publicly accepted as the latest technological advance, rather than an isolated oddity. Other manufacturers, already investing in the technology, would likely have followed Auburn and Hupp into the market, increasing the acceptance – and sales – of front wheel drive automobiles for all manufacturers.

Instead, Hupp’s sales continued to fall. Their new models differed little from the 1928 models. By 1931, sales had dropped to 17,450 automobiles. A fresh design by Raymond Lowey for the 1932 models came too late to make a difference. Hupmobile sales fell to 10,467 and then fell to 7,316 in 1933. Hupp offered another Lowey redesign for 1934 in it higher-priced line and introduced a low-priced model using modified Ford bodies built by Murray under license. Sales increased to 9,420 automobiles.

In the six years after Hupp’s management rejected Archie Andrews plan, Hupmobile sales dropped more than 85%.

In a span of six years, Hupp management, to borrow Mr. Richardson’s phrase in Hemmings, ran Hupp “into the ground.” As we shall see later, that is where Archie Andrews found it in 1934.

Hupp was one of the three failing car companies that killed the Ruxton.

Denied production facilities and a dealer network by Hupp’s management, Archie Andrews formed his own corporation to manufacture the Budd prototype. The name he gave the company illustrates what he thought of the venture: New Era Motors, Inc. The automobile was named “Ruxton,” after one of the initial New Era board members.

Andrews also hired William Muller away from Budd to join New Era and complete production engineering for the Ruxton.

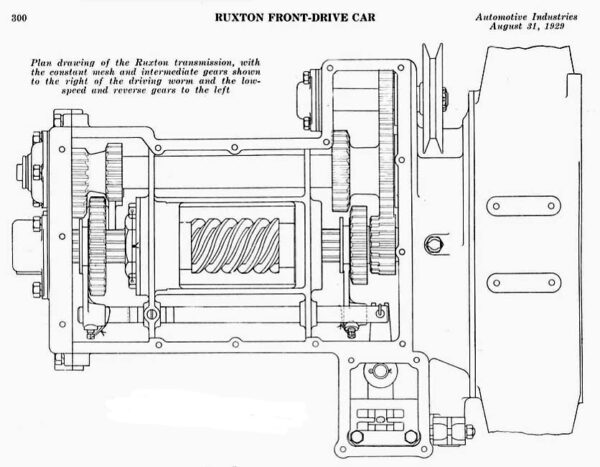

The Budd prototype had the same traction problems as the L29 Cord – and for the same reason: making space for the transaxle ahead of the engine shifted too much weight toward the rear. Muller solved those problems by designing a unique transaxle. His design split the transmission, with first gear and reverse ahead of the drive and third and fourth gears behind it, driving through a worm gear and wheel instead of a conventional ring and pinion. This compact transaxle allowed positioning the engine further forward. As a result, the Ruxton suffered only a three percent traction loss on a fifteen percent grade.

New Era needed a facility to assemble the chassis and produce the transaxle designed by Muller and it needed dealers to sell the Ruxton. It had other elements required for production in place from the outset: Budd would build the bodies and Continental would produce the engines.

In June of 1929, Gardner Motor Company announced it would build the Ruxton. Gardner had previously contracted with General Motors to produce Chevrolets and its President, Fred W. Gardner, was a member of the initial New Era board of directors. With its General Motors contract ended, Gardner was left with a plant capable of producing 40,000 automobiles a year, in which it was producing only 4,500 Gardner automobiles yearly.

Then Gardner backed out. The company founder’s son later claimed Andrews had not made the initial payment required. Maybe – but it appears Fred W. Gardner had taken advantage of his membership in the initial New Era board of directors to plan Gardner’s own front wheel drive vehicle. It would be announced as a 1930 model. Perhaps Gardner rejected the Ruxton to avoid eclipsing their own car. (If so, it did not work out well for Gardner. The company would voluntarily liquidate its assets and go out of business in 1931.) Upon Gardner’s withdrawal, Andrews next attempted to reach an agreement with Marmon Motor Car Company. However, that agreement depended on an exchange of New Era and Marmon stock. The 1929 stock market “crash” intervened just as the negotiations were being finalized. Marmon’s stock lost its value in a matter of days and that deal was stillborn.

Andrews next reached an agreement with the Moon Motor Car Company for production of the Ruxton.

Andrews is accused of destroying Moon, too.

He did not – as we will see in Part Two.

Moon is the second of three failing car companies that killed the Ruxton.

CONTINUED IN PART TWO

Pingback: HOW THREE FAILING CAR COMPANIES KILLED THE RUXTON - PART TWO – Automobile Chronicles