One hundred years ago, many automobiles were produced from standardized components purchased from others, rather than from components manufactured in house by the automobile company. Comprising 25% of the new car market in 1916, these were called “assembled cars.” Production costs drove most assembled cars from the market during the 1920’s. None survived the onset of the depression. Today, however, the “assembled car” may be making a comeback – as an “EV.”

Shortly after leaving General Motors, Johan de Nysschen, formerly in charge of Cadillac and now Chief Operating Officer of Volkswagen of America, was interviewed by Automobile Magazine. He was asked about the impact of the electric vehicle (EV) on established automobile manufacturers. De Nysschen explained that “[t]he ability to differentiate is far more challenging when it comes to EVs than it is with internal combustion because the complexity of the [internal combustion] mechanical system is what creates a better mouse trap. It’s far more . . . ubiquitous with EVs. You know, you have electric motors. And an electric motor is an electric motor. A battery’s a battery. Now, I don’t want to oversimplify. You’ve got your [battery] chemistry. You’ve got more sophisticated motors, but still generally speaking, the differentiation is far lower.

“You could as an automaker decide to invest in mastering, in-house, all of this capability to develop your own batteries and the intellectual property to your cell chemistry. And what can happen is that the entire supplier industry—which between them probably have more investment resources than any single automaker—might come up with a better technology. You’ve just invested in a dead end.

“Now, if you for that reason decide it might be smarter and less risky to partner, . . . if you end up outsourcing all of this technology, you eventually become just an assembler. It’s a very complex set of circumstances that you have to manage about how much to invest, the return on the product, how much do you reuse components. It’s entirely a new ballgame.”

Well, not really.

It is exactly the same ballgame automobile manufacturers were playing one hundred years ago. Then, as now, there was one big advantage to producing an assembled car and one big disadvantage. Both were tied to cost.

The advantage of producing an automobile from outsourced standardized components is lower capital investment. The company is spared the expense of engineering the components and tooling for their production. Ultimately, this means it requires less capital to enter the market with a new vehicle than it would if everything were designed and manufactured in-house. In turn, that allows available capital to be directed to areas, such as marketing, that are critical to sales and to start the flow of revenue into the company.

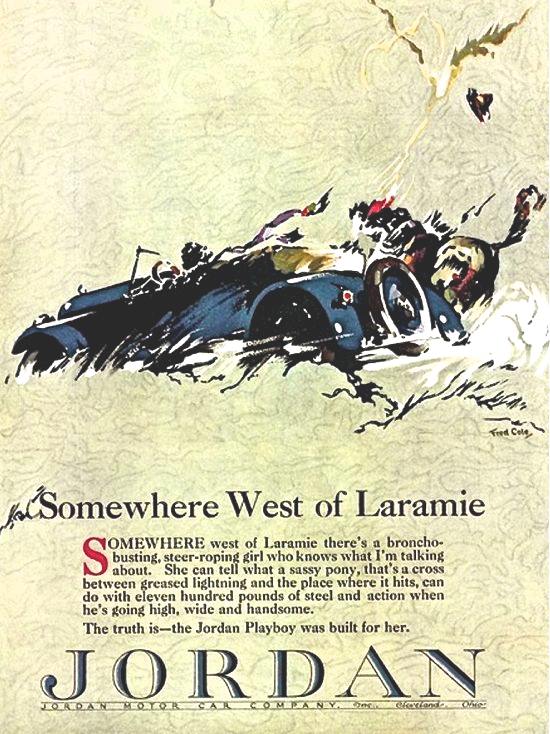

An illustration is the Jordan, produced from 1917 to 1931. Today, Jordan is perhaps best known for the Jordan Playboy model and Jordan’s “Somewhere West of Laramie” advertisement – an ad commonly credited as the first designed to sell by evoking an image, rather than merely reciting an automobile’s attributes. The Jordan, however, was the prototypical “assembled car.” As James H. Lackey wrote in his book, The Jordan Automobile: A History, “It would have been impossible to start a company which manufactured all of its components in house with only $800,000. Assembled automobiles were the only alternative.” The company’s founder, Edward “Ned” Jordan, was rather blunt about it: “We never were automobile manufacturers,” Jordan wrote in his autobiography, The Inside Story of Adam and Eve. “We were pioneers of a new technique in assembly production, custom style sales and advertising. We had one air compressor to power the assembly line, bought only the finest component parts from the most experienced quality parts makers, designed a chassis for those parts that possessed the most ideal weight distribution yet attained. Then we ‘dolled them up’ just as every good car is dressed today.”

Jordan reached its peak production of 8,469 automobiles in 1926. By 1928, however, Ned Jordan began liquidating his interest in the company. A new model had flopped, eating up profits. Perhaps most importantly, however, large automobile manufacturers were now financing dealer inventories, which Jordan could not do. His timing was fortunate. In 1952, Mr. Jordan told Advertising Age, “Thank the Lord we quit just in time. Our families have since been enjoying the trust funds which the Playboy earned.”

The Jordan illustrates both the advantage and the disadvantage of an assembled car. As Mr. Jordan’s reference to trust funds implies, it was an approach that could be highly profitable. But, as the company’s ultimate demise also illustrates, it is an approach that is highly vulnerable to the underlying costs of production.

It is no accident that the “assembled car was typically a medium-priced automobile, rather than a low-priced competitor to Ford or Chevrolet. Because components of an assembled car were purchased from third parties in lower quantities, those components cost the company producing an assembled car more than equivalent components cost a manufacturer producing those components itself, in-house and in volume. That made the assembled car more expensive to produce, a disadvantage more easily absorbed when selling automobiles at higher price points.

In reality, the manufacturer of an assembled car did not avoid the expense of manufacturing components – it has merely shifted the time when those costs were paid. Instead of investing up-front in design and tooling, the manufacturers of assembled cars were on a pay-as-you go plan, one that added a carrying cost to the ultimate price paid for components.

The producer of an assembled car also lost any opportunity to argue its design was superior to that of a competitor. There was nothing unique about the components of an assembled car, no unique engineering proprietary to the brand about which the company could boast in its marketing. Most assembled car brands advertised the specifications of their vehicles without disclosing the actual manufacturers of its components. Without the advertising genius of a Ned Jordan to sell on image, that meant there was little difference between the specifications of an assembled car and that of its competitors. There was, consequently, nothing unique to the brand in its marketing.

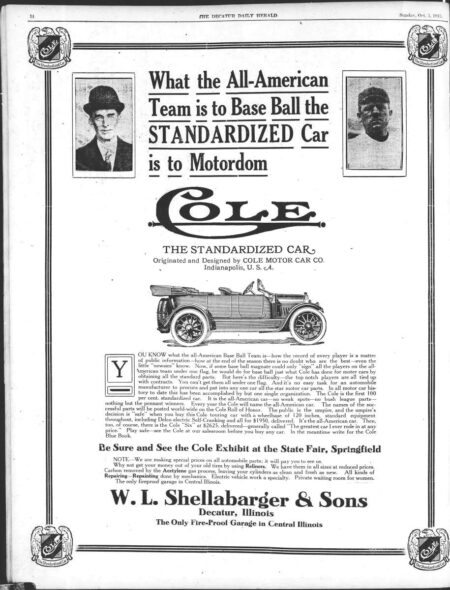

A few producers of assembled cars chose to confront this problem directly and overtly market their product as better than other brands because built of better components. Their argument was that they combine the best components available to produce a superior automobile.

A 1917 advertisement for Biddle took this approach, prominently featuring its superior “Duesenburg Motor.” Cole advertised its assembled car as the “standardized car.” In so doing, Cole was using the word “standard” exactly as Cadillac did when it referred to itself as the “Standard of the World” or John Rockefeller did when naming his kerosene company “Standard Oil.” “Standard” meant the perfect measure, the standard against which anything of the same type was to be measured. Cole argued that it produced a product superior overall because each of its subsidiary components was made by a manufacturer expert in that component – the automotive equivalent of a baseball team comprised of only the best players. Cole did buy the best – it even sourced its V-8 engines from the same General Motors subsidiary that manufactured the Cadillac V-8. But Biddle ended its production in 1922. Cole ceased production in 1925. The cost of components against the price it could charge in the market drained the profit from the enterprise.

There was another problem for the producer of an “assembled car.” Producing an automobile from off-the-shelf components manufactured by others meant the vehicle was assembled from major components that had not been designed for it.

Writing in the Horseless Age magazine in December of 1909, Mr. E. J. Bartlett described the pitfalls that awaited the novice producer of an assembled car: “The principal parts once secured, the engineer can turn his attention to details of their construction which previously he has been, to some extent, obliged to neglect. He finds, for example, the hub caps on the front and rear axles do not match, that his front hubs come drilled for twelve spokes and his wheels with ten spokes; that the steering arm on the front axle has a one inch ball, and on the steering column lever a 1 1/2 inch ball; water piping on the engine doesn’t match the radiator, the universal joint doesn’t fit the pinion shaft on the axle, and the rear bearing of the transmission is not large enough to take the torque of the braking and driving strains. It seems that nothing is properly designed, and he blames the parts makers for their seeming inconsistency, and yet they are naturally furnishing what their experience shows is most generally required. The inherent trouble lies in the fact that the various parts were not designed to be used together.”

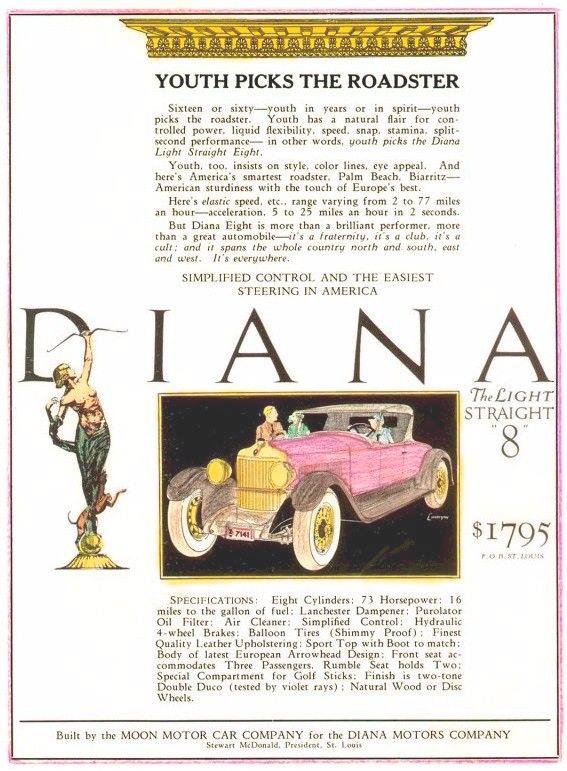

One of the most vivid illustrations of failure to design a vehicle to suit its components, or vice-versa, is the Diana. In mythology, Diana is goddess of the Moon. The Diana automobile was an assembled car introduced in 1925 by a subsidiary of the Moon Motor Car Company. Its engine was sourced from Continental Motors Company – a major supplier of engines for assembled cars, including Jordan. Unfortunately, whether due to Continental’s design of the engine or Moon’s design of its cooling system, the Diana’s engines were prone to overheat. The resulting warranty claims destroyed the Diana’s reputation in the market and production ended in 1929. (For more on Moon Motor Company, see our post about Moon and the Ruxton.)

One of the most vivid illustrations of failure to design a vehicle to suit its components, or vice-versa, is the Diana. In mythology, Diana is goddess of the Moon. The Diana automobile was an assembled car introduced in 1925 by a subsidiary of the Moon Motor Car Company. Its engine was sourced from Continental Motors Company – a major supplier of engines for assembled cars, including Jordan. Unfortunately, whether due to Continental’s design of the engine or Moon’s design of its cooling system, the Diana’s engines were prone to overheat. The resulting warranty claims destroyed the Diana’s reputation in the market and production ended in 1929. (For more on Moon Motor Company, see our post about Moon and the Ruxton.)

Nonetheless, these were pitfalls that could be avoided. As Mr. Bartlett noted in the conclusion to his article, were a company to chose carefully among the components available and properly engineer its product, then “with sound financial backing, there is no doubt that the assembled car can be made a success.”

Today, it is conventional wisdom among all established automobile manufacturers that the electric vehicle is the future of the automobile To some extent, this results from government policies in China and the European Union that promote production of electric vehicles. Consequently, major automobile manufacturers are investing billions into electric battery research. No automobile executive wants to be the one that missed the EV boat.

Even so, these same manufacturers and executives are facing new and unwelcome potential competition. Producing an assembled car may, once again, make economic sense – and present a challenge to established automobile manufacturers that they may not be equipped to meet.

Unlike the situation a century ago when large automobile manufacturers held a technological and cost edge in development of internal combustion engines and drivetrains that assembled car producers could not match with outsourced components, today the established automobile manufactures are faced with another established industry that is already engaged in advanced development of electric drivetrains. It is the large battery manufacturers who have the head-start in developing the battery technology upon which the future success of the EV depends. As reported by the Korea Times, three companies – LG Chem of Korea, Panasonic of Japan, and Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) of China – together hold 70% of the current EV battery market, with Samsung recently announcing advances in solid state battery technology that could provide a 500 mile range, very quick charging times, and a battery life of 500,000 miles.

There is no reason to believe these battery manufacturers intend to cede that market to anyone else, or that the current automobile manufacturers can create battery technology that is superior. These battery manufacturers will continue to be major suppliers for EVs, and very possibly the dominant suppliers.

That creates, again, the opportunity for successfully producing and marketing an assembled car.

Today, as Mr. De Nysschen’s comments imply, new EV producers may be able to source electric motors and batteries competitive with those of established automobile manufacturers. These new EV producers will need less capital to enter the market and still be amply financed to effectively market their product – just as Jordan did in its day. They will have advantages that the assembled car producer of a century ago lacked. The components they may be able to purchase may exceed the technological sophistication of automobile manufacturers keeping manufacturing in-house. Private equity funds now create access to credit for financing inventory and consumer sales unimaginable in the 1920’s. The new producer of an EV may also be able to create an image of exclusivity for its products, a natural avenue for promoting a smaller production volume.

The “assembled car” may be about to make a comeback.