ALVAN MACAULEY SQUANDERS

PACKARD’S CAPITAL, WITH LASTING EFFECT

In his Octane magazine column, Jay Leno recently wrote that “one of the final nails in the coffin [of Packard] was bringing in James Nance – a man with absolutely no experience of automobiles who came from a background of selling appliances.” It’s a common myth, one not unique to Leno. But it’s wrong. Nance didn’t kill Packard. He saved the company, even though he couldn’t save the brand.

On March 1, 1954 – less than two years after James Nance became President of the Packard Motor Car Company – its treasurer, Walter Grant, wrote a memorandum to him: “Basically, the company is rapidly approaching bankruptcy.” Grant predicted that, absent decreases in expenses, working capital would be exhausted by the end of June, 1955. He concluded by advocating merger with one of the two remaining independent automobile manufacturers.

In 1955, the now combined Studebaker-Packard Corporation posted a loss of $29,705,093.

In 1955, General Motors became the first corporation in history to report a profit for a single year exceeding, $1,000,000,000 – as in one billion dollars.

It is laughable to blame James Nance for Packard’s demise.

Packard was doomed long before Nance became its president.

Yes, but did not the ‘merger’ with Studebaker – it was technically an acquisition of Studebaker by Packard, not a merger – kill Packard? And wasn’t Nance responsible for the merger?

No, and no.

Combining with Studebaker was a desperate move by Packard’s board of directors and management, including but not limited to Nance, to save a doomed company. They didn’t bother with what we’d today term “due diligence,” did not audit Studebaker’s books, or verify its financial representations. None of that really mattered. They were hoping for a miracle. Without one, they knew their company would die. There was only one avenue that presented any hope of a different outcome, so they – quite logically – took that chance. It turned out that the hope was really a chimera, a financial mirage that disappeared almost as soon as the deal was done. But you cannot fairly blame Nance for any of this. What he did, or did not do, was largely irrelevant to Packard’s demise.

To understand why Packard failed it is necessary to go back to its earlier near-death experience during the financial depression of the 1930’s. In the four years before Packard’s introduction of the One Twenty model in 1935, the Packard Motor Company lost $16,400,000. Introduction of the One Twenty produced instant profits, saving the company from an otherwise inevitable bankruptcy.

The One Twenty was neither a new idea nor a brilliant one. Alvan Macauley, the company’s president at the time and the man who committed the company to building a modern facility for mass production, had long sought to push Packard down market to increase its customer base and its sales volume. Adopting mass production methods allowed him to do just that.

There are those – and were even among holdovers within Packard’s management during the 1950’s – who believe the One Twenty “cheapened the brand.” To them, the One Twenty precipitated a chain of events ultimately resulting in Packard’s downfall.

They are wrong.

The problem was not cheapening Packard’s image, per se. The problem was the failure of Packard’s management to understand the market into which they were now selling mass-produced automobiles and to properly position the Packard brand in that market. That failure, in turn, was the product of a risk-adverse corporate culture that focused on avoiding debt and thought of profit only in terms of operating profits, rather than appreciating that any model’s price must contribute to covering the costs of developing its replacement if the company is to be truly profitable.

When we think of Packards of the classic era – what were then considered Senior” models, in contrast to the “Junior” models initiated with the One Twenty – we think of automobiles produced by craftsmen machining chassis parts and producing wood-framed bodies. These were automobiles produced by obsolete technology, even in their most halcyon days. In the 1930’s, labor was plentiful and, consequently, inexpensive. It was machines that were expensive. When production volume was low, it made economic sense to manufacture with cheap labor rather than expensive machines. The cost of machine tools could not be profitably amortized over low production volume.

By the 1930’s, however, production techniques had advanced to the point that mass produced automobiles could equal or exceed the quality of those manufactured mostly by individual labor. Welded steel bodies did not develop squeaks over time. Bespoke bodies framed with wood did. Quick drying automotive paints were available for mass produced automobiles and allowed customers to select colors to suit their individual preference. Custom manufacture was no longer needed to produce automobiles that were individually distinctive. Technology always improves as it evolves and mass-produced automobiles became more refined with improved performance during the 1930’s.

America’s social structure was also changing, as the middle class grew in size and regained prosperity.

There had always been an upper middle class. Packard had catered to that clientele – successful doctors, lawyers, and merchants – during the two decades before the Depression. It was to these customers that Packard had sold most of its production.

These were the customers Packard had lost during the first half of the 1930’s. The Depression took away their prosperity. Even those who could still afford to purchase a Packard found it financially prudent not to. With mass-produced automobiles proving a less expensive alternative, in the first half of the 1930’s Packard’s labor-intensive product line no longer offered an automobile for this clientele.

The One Twenty was actually Packard reaching out to this lost clientele.

This was not “cheapening the brand.” The One Twenty was not an inexpensive automobile. This was reintroducing Packard to the upper middle class clientele upon which it had always depended.

It was after introduction of the One Twenty that Packard’s management fumbled, the first in a series of unnecessary and stupid errors by Packard management that doomed the company before James Nance would try to save it.

Introduction of the One Twenty swung Packard from a loss of over $7,000,000 in 1934 to a profit exceeding $3,000,000. Profit reached $7,000,000 in 1936, before dipping to approximately $3,000,000 in 1937.

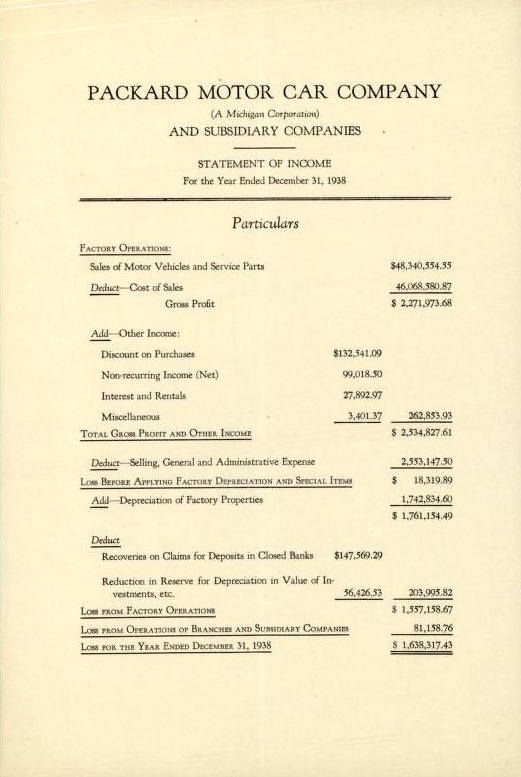

By 1938, Packard was again reporting a loss.

As a previous post discussed in greater detail, Macauley was not brilliant for introducing the One Twenty. He was stupid for continuing the Senior models in production. Every penny of the losses from 1931 through 1934 were attributable to those models, so it is fair to assume that they continued to lose just as much money in the following years, if not more. That means Packard squandered over $20,000,000 in profits from the One Twenty on the Senior models from 1935 through 1938.

That’s an astonishing amount of money.

It also money Packard should have spent on its future, rather than its past.

This, then, was the beginning of the end for Packard.

There was a lesson to be learned in the One Twenty’s success, but it was a lesson that Alvan Macauley and Packard management ignored. That the market for hand-built bespoke bodied prestige luxury marques had all but disappeared was obvious. It was also clear, for anyone caring enough to pay attention, that the increasing quality of mass produced automobiles had eliminated much of the quality advantage once enjoyed by automobiles produced at great cost by hand craftsmanship.

These realities were in plain view at the Packard Motor Company. To produce the One Twenty, it had been necessary for Macauley to create from scratch a mass produced automobile – one using a new, state-of-the art assembly plant to manufacture automobiles in volume, automobiles that had been engineered specifically to be produced by assembly line methods. That modern facility existed at the same address as the one that produced the Senior models by the same labor intensive methods Packard had used for decades.

It must also have been obvious that the One Twenty would be facing serious competition. Using the Packard name on the “Junior” line was a marketing and financial necessity. Companies that had introduced less expensive automobiles under a different brand had largely failed to sell them, losing even more money in the process. Packard needed to trade on the value of the Packard name to assure sales of the One Twenty. But the continued value of that name – its prestige – ultimately would depend on the success of this “Junior” line. Unless those cars were leaders in quality, technology, and value, the supposed prestige transfer from Packards sold to the ultra-wealthy would prove meaningless.

Mistakes of vision are commonly excused by noting that ‘hindsight is always 20-20.’ When offered as an excuse for mismanagement, that is not an acceptable explanation. The function of corporate management is to have vision, to anticipate the future, to anticipate the market, to consider what might occur and plan for the possibilities – and plan how best to profit in each scenario.

With the One Twenty, Packard – apparently by simple luck born of necessity – had stumbled upon the emerging luxury automobile market that would blossom in the years following World War Two. That luxury market was not the ultra-rich. It was the upper middle-class. Nothing suggests Macauley or anyone else in Packard’s management saw that this emerging market existed.

Others were not so blind. Lincoln introduced the Zephyr in 1936. It was priced at about $1,300.00 and equipped with a flathead derived V-12 engine. Cadillac introduced the model 36-60 that same year. Equipped with a smaller bore version of the V-8 used in larger Cadillac models, the 36-60 was priced at $1,645.00. In its first year, the “Sixty Series” accounted for half of all Cadillac sales. These were automobiles with the same prestige nameplates as earlier more costly models but were offered at a price aimed squarely at a prosperous middle class clientele looking for a modern luxury automobile. These were automobiles competing in the market at which Packard, who priced the One Twenty at from $995.00 to $1095.00 at its 1935 introduction, should have been aiming.

What Macauley should have done was use the profits from the One Twenty to develop and market future models aimed squarely at this upper middle class market – a market that was a natural one for Packard.

What Macauley did do was milk the One Twenty and Packard’s image in the following years with progressively less-expensive models offering fewer features and increasingly dated styling – for example, introducing six cylinder models below the eight cylinder One-Twenty, sharing its appearance but priced lower. MacCauley was constantly pushing the brand down market.

This, then, was the true “cheapening of the brand.”

Though Packard did not break out profit and loss by model range, it is evident from events that Packard used the One Twenty’s profits to subsidize continuing production of the “Senior” Packards – squandering those profits by so doing. It was not until April of 1941 that Packard introduced a model with new and modern styling and a more modern chassis, the Clipper. Even then, the Clipper carried over the same straight eight cylinder engine and drivetrain originated in the 1935 One Twenty.

In truth, Packard’s supposedly conservative management was disastrously reckless. Introduction of the One Twenty had changed the nature of the company. It had been the manufacturer of small volumes of labor intensive luxury automobiles for an exclusive clientele, a market in which it dominated. It was now a manufacturer of mass production automobiles competing in vastly larger market, one in which it had a relatively small share. Every resource at the company’s disposal should have been devoted to achieving success in the market in which it could naturally have dominated – the emerging upper middle class market for mass produced luxury automobiles.

Continued in Part Two

See also previous posts: The Real Reason Packard Died and Pat Foster and the Myths of Packard’s Demise.