MACAULEY’S GHOST KILLS PACKARD’S LAST CHANCE

MACAULEY’S GHOST KILLS PACKARD’S LAST CHANCE

Barely five years after Packard invested in a new plant to manufacture bodies for the One Twenty, Macauley was outsourcing body production for the Clipper to Briggs Manufacturing Company. Although this was justified at the time as an expedient to get the car into production because Packard’s own facilities were at capacity producing bodies for existing models, the explanation is suspect. It is always less expensive to produce automobile bodies in volume in-house. Subcontracting volume body production occurs when companies lack the capital to invest in their own production facilities and tooling. Regardless of the ostensible justification, they end up paying more. The company shifts the capital expense to the subcontractor. The subcontractor rolls that capital expense into its price, plus a markup for its own profit.

If, however, if a company does not have the capital required to produce in-house, it doesn’t have a choice.

It is realistic to ask whether anything Packard did after the end of World War Two could have continued the company in the automobile business as a long-term going concern. Macauley’s pre-War decisions not only squandered its profits, but also created a risk-averse corporate culture that prioritized cash over investment and avoided debt at all costs.

The consumer market for automobiles changed enormously during the War. Those changes would continue after the War ended.

Between 1939 and 1945, the average family income almost doubled. At War’s end, people had money and were no longer afraid to display their wealth. The middle class was becoming the dominant segment of the American populace, and the upper-middle class had increased exponentially. The market for automobiles was similarly transformed. In 1948, 60% percent of United States households owned an automobile. In 1955, it was 90% percent. Between 1946 and 1955, the number of automobiles manufactured annually in the United States quadrupled. Even more importantly for a brand aimed at the upper middle class, by 1956 the majority of jobs in the United States were “white collar.”

Macauley had hand-picked George Christopher to succeed him as company president in 1942, with Macauley continuing to control the company’s decisions as Chairman of the Board of Directors until he finally left the ship he’d torpedoed, by retiring in 1948. Together, these two crushed whatever post-War chance Packard had for long-term survival by continuing Macauley’s pattern of reckless decisions masquerading as prudent finance.

General Motors introduced the Hydramatic fully automatic transmission in the 1940 Oldsmobile. Cadillac offered it as an option for the 1941 model year to instant success: 30 percent of new Cadillacs were so equipped at an option cost of $125.00. Cadillac introduced a completely new and modern body design for Cadillac in 1948 and followed it in 1949 with an all-new modern high compression V-8. Mid-year in 1949, Cadillac would introduce a pillarless two-door hardtop. None of this was occurring in secret – Packard, in common with the other automobile manufacturers, were fully aware of what General Motors was doing.

Yet Macauley and Christopher stuck with same straight eight engine first used in the One Twenty. Packard’s belated attempt at an automatic transmission was the Ultramatic introduced in 1949. Similar enough in design to Buick’s Dynaflow that General Motors sued for patent infringement, the Ultramatic was a mediocre design. It could not actually shift gears. Rather, it started in the second of its two gears varying speed through the torque converter. The result was slow acceleration. (It would be 1955, after Nance had made it a priority, before Packard’s automatic could shift gears – too late and beset by quality problems.)

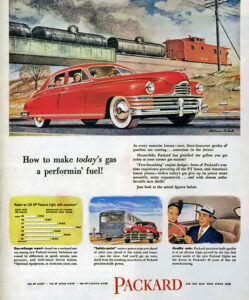

And then there’s the “bathtub.”

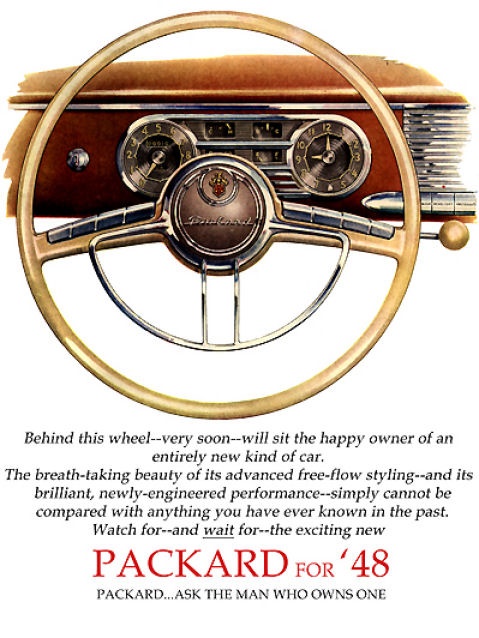

Though the design department at Packard had created the design of a fully new model and Packard had the financing in place to develop it, Macauley and Christopher rejected all proposals for a new post-War design. Instead, they accepted Briggs’ proposal to produce a facelifted pre-War Clipper. That facelift, ironically, ultimately cost enough in new tooling that the savings over a fully new body design were insignificant.

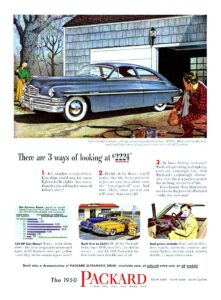

Even as competitors’ truly new models were introduced and Packard sales sank, Christopher still refused to spend the money to develop an entirely new model – which condemned Packard to keep the bloated “bathtub” in showrooms for 1950.

Christopher had been in charge of production as Macauley had driven the Packard brand down-market in the 1930’s, lowering prices and decontenting the product throughout the period in an effort to avoid the consequences of starving the product line of investment. As company president following the War, he pursued that same strategy. Packard had recruited new dealers after the War with promises of volume sales – promises that were foolish when made and would be rendered impossible to keep with a dated product subcontracted to an outside supplier.

Christopher’s mindset as Packard president was that of a production man, which is what he’d always been. To him, fixed costs are spread out over production. The higher the production, the lower the fixed cost per vehicle produced. Thus, if you are losing money on existing volume, the way to reduce that loss or turn it into a profit is to increase the volume. You must sell what you produce, so this means increasing sales. To increase sales without having to invest in anything new, you must decontent existing models and sell these de-contented models at a lower price. That spreads fixed costs over greater volume and if the total income from sales exceeds the fixed costs and costs of production, you can claim an operating “profit.”

This is a strategy that postpones doom while still making the balance sheet look good.

The problem with this strategy is that the same reasons people did not want to buy your existing models will ultimately lead them to reject cheaper models that offer even less. It is a strategy that can succeed only for a short time. If you are using that strategy to buy time while simultaneously developing new products and bringing them to market, it may work. If, however, you are doing this only to tread financial waters, the strategy is ultimately its own undoing and the company then drowns in red ink.

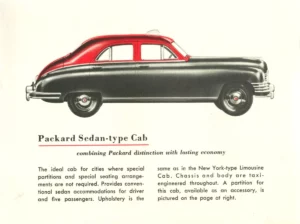

Christopher – while Macauley was still Chairman of the Board – even reduced Packard to the level of selling models specifically designed as taxicabs. It was a decision bizarrely blind to Packard’s place in the luxury market. This was merely one of the many short-sighted and ultimately disastrous decisions Christopher and, looking over his shoulder, Macauley would make in the years following the end of World War Two. Nance would be the one to deal with the consequences.

Christopher’s focus on production appears to have blinded him to nature of the post-War automobile market. The reluctance to invest in a fully new Packard following the War has been attributed to a fear by Packard management – ever in the thrall of Macauley’s corporate risk-averse culture – that the seller’s market existing immediately after the War would become a buyer’s market once the market for new cars was satiated. Hence, fearing a decline in the market, Packard avoided capital expenditure by turning all body production over to Briggs and withholding investment in a new model with modern drivetrain and chassis.

The excuse doesn’t hold water. This was a strategy that was designed to keep the company in the black for the benefit of its officers, not to keep the company alive and prosperous into the indefinite future. Packard in this period was completely controlled by Macauley. It’s management was in the care off officers selected and promoted to their present positions by Macauley or with his assent. There was no corporate pension plan, no retirement fund. They were paid only while the worked. So, they stayed.

When your livelihood depends on a company’s continued existence, you will be reluctant to take any step that might put that existence at risk in the near term. Consequently, Packard’s management was not a group disposed to take risks, in business or in their personal lives. These were men imbued with the Macauley corporate culture, one that husbanded cash, avoided debt, and considered both the epitome of prudent management.

Against this background, the decisions made by Packard management in the years following World War Two are understandable. Being understandable does not, however, make them justified or right. We can understand murder, but we don’t condone it.

Packard’s management should have known – since all the other automobile manufacturers did – that in a buyer’s market that you must have the newest, most advanced, most modern, most innovative, and highest quality product to have any chance of succeeding. If you do not, selling on price will not save you. It especially will not save you in an economy of rapidly expanding prosperity where the product is highly visible and publicly reflects your social status.

This is not a lesson that Christopher, or anyone else in Packard management, should have needed to learn.

Intentionally continuing an obsolete design with full awareness that the competition would be introducing new models with new designs and advanced technology was an inexcusable decision. Macauley would eventually conclude that his selection of Christopher as successor was a mistake, a useless belated recognition of error designed to obscure Macauley’s unbroken chain of mistakes by blaming Christopher for the culmination of those mistakes.

Yet, Christopher has a defense.

He didn’t have the money.

Packard’s financial situation had not been improved by the War. Packard could have realized more income by simply parking its funds in War bonds than it did by manufacturing under wartime cost-plus contracts. The company entered the War undercapitalized and it exited the War even more undercapitalized.

Post-War, Packard may have been unsustainable as an automobile manufacturer, no matter what it or its executives did.

Packard in the immediate post-War economy was a pipsqueak among automobile manufacturers. Other manufacturers made the huge investments necessary to produce entirely new vehicles in competition with General Motors, Inc., Ford Motor Company, and Chrysler Corporation. None succeeded.

There is a reason.

In 1948, General Motors profit was $440,447,724. The next year, 1949, its profit was $656,434,232.

In 1948, Packard reported a profit of $24,789,439. In 1949, as the “bathtub” effect set in, Packard’s profit was $13,406,042.

In these numbers, we see the impact of Macauley’s pre-War decisions squandering Packard’s profits and its position in the emerging luxury automobile market. It was only in 1949 that Packard finally decided to develop a new body design – a board of directors rebellion that would ultimately force Christopher to resign to force that decision. Packard would end up telling its shareholders in the company’s annual report that the company’s $0.50 per share dividend would be suspended in 1950 to allow for the “outlay of substantial cash for tools and equipment during the first half” of that year.

In other words, with two percent of General Motors’ profits, Packard was going to continue to try to compete with it.

Macauley would retire in 1948, leaving to his successors the dismal task of presiding over a company that could not survive, but that they would nonetheless try to save.

Continued from Part One

Continued at Part Three

See also previous posts: The Real Reason Packard Died and Pat Foster and the Myths of Packard’s Demise.

MACAULEY’S GHOST KILLS PACKARD’S LAST CHANCE

MACAULEY’S GHOST KILLS PACKARD’S LAST CHANCE