JAMES NANCE: THE RIGHT MAN ARRIVES TOO LATE

James Nance would become Packard’s president on May 1, 1952.

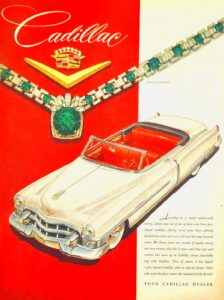

By then, the image of Cadillac as the prestige American automobile was cemented in public perception. On November 5, 1953, a new Broadway production opened at the Belasco Theatre in New York City: “The Solid Gold Cadillac.” It would run for 526 consecutive performances, closing on February 12, 1955, and become a hit movie the following year. The title came from the gift given the hero and heroine at the end of the play – the most prestigious gift conceivable: a solid gold Cadillac. In the public mind, though, the ‘solid gold’ was almost superfluous. Everyone knew Cadillac was the best.

The new model Packard had introduced for 1951 did not have a V-8 engine. It did not have an automatic transmission capable of shifting gears. The bodies were produced by Briggs, not by Packard. It did not reposition Packard as a luxury, rather than mid-priced, brand.

It was, however, with that new model that James Nance was hired to rescue Packard.

Nance came aboard with some of the work already done. The president who replaced Christopher at Packard, Hugh Ferry, had taken several steps in the ‘better late than never’ category, decisions that should have been made by Macauley and Christopher. In January of 1952, he’d secured approval for development of a Packard V-8 engine and construction of a new plant to manufacture it (though the costs were not actually budgeted until after Nance became president). He introduced Packard’s own two door hardtop, the Mayfair, in February of that year. It was Ferry who bought the rights to the torsion bar suspension system that would be introduced while Nance was company president.

Yet the legacy of Alvan Macauley and the perpetually capital starved Packard Motor Company he left to his successors influenced even Ferry, though Ferry fully understood the necessity of Packard catching up to its competition to survive.

Ferry had become Packard’s president because someone had to do it and Christopher’s forced departure had occurred suddenly, leaving no time to plan for succession. Ferry, from the outset, regarded finding his replacement as his top priority. In the meantime, however, he needed to keep the company alive. His background was in finance – he’d started as a cost accountant, risen through the ranks to become corporate Secretary and Treasurer, then Vice-President. He knew as well as anyone the financial condition of the company, the impact of its dismal sales, and the capital expenditures required in the next few years to manufacture new models with modern features.

In short, he knew he needed money.

Ferry took advantage of the government’s need for manufacturing capacity to fight the Korean War and contracted with the United States government to produce diesel engines and the General Electric J-47 turbojet engine. He expected profits from the government contracts would underwrite the costs of modernizing Packard’s automobile line. The contracts would potentially generate income (i.e., gross sales, not net profit) of $200,000,000 a year. A steady flow of profits from those contracts would buy Packard time, financing the ongoing costs of new models and new features and giving Packard the lifeline it needed to keep going until the sales of those new models could sustain it.

Unfortunately, these contracts required that Packard make the investment necessary to produce the products contracted, including building a new manufacturing plant. This meant Packard was spending its capital – $17,000,000 of it in total – now and up front. Ferry viewed that as a down payment on a much larger stream of future revenue. But it was also meant depriving the automobile business of that same money – to the detriment of the product line the defense business was intended to succor.

In this decision, we see the ghost of Alvan Macauley still haunting Packard.

As he likely saw it, Ferry had two choices. He could commit the money for capital expenditures needed to fulfill the contracts. Or he could put that money into the development of new models, powertrains, and features for Packards that would be introduced in the coming years. The later choice gambled that the company could keep going until it could catch up. The former promised a revenue stream that would buy the time needed to catch up.

He chose the former.

But there was a third choice.

To raise additional capital to finance the investment needed for the defense contracts, Ferry could have borrowed the money or he could have issued new stock in the company.

He should have done one or the other, or even both.

Borrowing to finance the defense contract investment should have been easy. Packard was debt-free, reported profits in its annual reports, and the contracts themselves promised a guaranteed revenue stream that would easily repay the principal and interest of the loan. Issuing stock might have presented more complicated issues, as it would have been viewed as diluting the value of currently issued shares. But there was a clear rationale for a new issue of stock to finance entry into a new business that promised to increase overall corporate profits to the benefit of all shareholders.

By the early 1950’s, the automobile industry – led by General Motors – was evolving into a three-year model replacement cycle. A new model would be introduced, slightly face lifted the second year, dramatically face-lifted in the third, and replaced with a completely new model the next year – and the cycle would start again. That completely new model might carry over the same engines and transmissions, but new tooling would be required for the rest of the car.

From a 2.5 percent share of the United States automobile market in 1948, Packard’s share fell to 2.1 percent in 1949, and dropped again to 1.7 percent in 1950. In 1951, Packard had a 1.43 percent share. The effect of this low volume impacted every aspect of its automobile business. Although it advertised much less, Packard’s advertising cost per vehicle sold was twice that of Cadillac. Having forsaken its own production facilities to subcontract body production to Briggs, its component costs for bodies were higher than its those of its competitors and it had less control over those costs. Its deal with Briggs still required it to pay for tooling, and that meant the cost of tooling per vehicle was higher, as well.

This was the point at which Packard needed to invest in its automotive operations. To do that, it needed all the capital it could muster. Ferry was probably correct in his belief that Packard needed the profits from the defense contracts to keep the company afloat while the company developed and introduced new models. But that process also required that Packard make a large investment now in the next generation of Packards that would be introduced. It needed to use the capital it had to develop new automobiles, not divert it to a government contract.

There is no indication that either borrowing or issuing stock were seriously entertained as options for funding the defense contract investment. Apart from War years, when Packard had incurred debt offset by receivables, Packard management financed development and production internally and avoided long-term debt. That culture, dating from Macauley’s years of control, appears to have limited Ferry’s perception of his options. He understood that he needed to consider the long-term. He appears not to have understood that there is an opportunity cost to financing internally and that it is sometimes better to rent other people’s money rather than risk your own.

Despite its competitive short-comings, the new Packard body design for the 1951 model year turned a loss in the first three quarters of the year into a $5,200,000 profit for the full year.

But it was a middle-priced car, not a luxury market automobile. The lowest priced model, the 200, accounted for 71,362 of the 100,713 automobiles produced. The top line Patrician 400 was almost indistinguishable in outward appearance from the 200 – and available only as a sedan. The car continued a straight eight engine and the Ultramatic transmission.

It was carried over with only minor trim changes as the 1952 and 1953 models.

In remarks delivered to a group of Packard executives shortly after his election as President, Nance made it clear that he understood where Packard stood and what it ought to do. He criticized outsourcing production, explaining it created a “vicious circle” of increased costs. He challenged a system in which design of parts did not consider cost – advocating “planning for costs.” He insisted that if parts were to be outsourced, the manufacturers of those parts needed to deliver the most advanced technology available.

He then turned to the public perception of the brand and what to do about it:

“To the man in his forties or over, Packard stands for quality. He still thinks of it as a quality car, an impression he got as a young man. But to the younger person of say thirty-five, Packard doesn’t stand for anything. Now, you ask the man on the street today, whether he is twenty-five, fifty, or seventy-five, what Buick stands for and you’ll get a pretty universal answer: it’s a good solid automobile in the upper middle price class. You ask what Cadillac stands for and every kid on the curbstone can tell you, ‘That’s the best, mister.’ Now we’re supposed to be in three of the five price classes, competing in the top bracket, for example, against Cadillac, the big Buick, and the two Chryslers, and we’re getting a miserable 3 ½ percent of that business. Packard! Three and a half percent.

“Now we must make a decision, gentlemen. And whatever that decision is, I’ll be damned if I’m going to be in a horse race and get left at the quarter pole. Let’s get in or get out. If we are going to make a quality car, then let’s get in the race, and if we’re going to abandon the field, then by God let’s do it with honor. Not by default.”

Nance’s remarks were somewhat self-contradictory. He acknowledged that Cadillac, not Packard, was perceived as “the best,” but professed to consider Packard still a competitor of Cadillac. He posited that Packard should not abandon the luxury field by default when his predecessors had already done precisely that. He was now faced with attempting a return to the luxury market with an automobile plainly produced for the mid-priced market.

The problem Nance faced was one that could only be solved with time. At best, the existing model dating from 1951 could be dressed up and efforts made to distinguish the Patrician version from the plebian one. But these could not fundamentally alter the product itself and, consequently, could only lay the groundwork for more dramatic differentiation in new models to come. Ferry had understood this. It was the reason he had invested in defense contracts that promised to bring Packard a constant cash flow to buy that time.

Nance immediately started the process of moving back into the luxury automobile market. He attempted to separate the premium models from those in the mid-price range, renaming the latter Clippers. To add glamour to the new premium line, he added the Caribbean convertible – at over $5,000 it was squarely in the Cadillac price range (though more directly competitive with the Buick Skylark). In an effort to match Cadillac’s most premium models, Packard introduced the Packard Derham – a custom formal sedan with an interior divider window separating driver and passenger compartments and padded leather top covering that was based on the Patrician – and contracted with Henny for production of long wheelbase sedans and limousines. (Derham was an established custom body builder dating to the classic car era of the thirties; Henney was the company that manufactured ambulances and hearses on Packard commercial chassis.) These were baby steps, but essential to reestablishing the name “Packard” as synonymous with “luxury car.”

Yet, to assuage dealer complaints, the distinction Nance was attempting to create was blurred. The company’s own consumer surveys had determined that the Packard name was important to retaining owners as repeat buyers. Understandably, dealers did not want the lower-priced line divorced from that name. Hence, the Clipper became the “Packard Clipper” in advertising.

The concession was probably considered of little consequence at the time. The 1953 Clipper and Packard shared the same body – they were obviously the same basic car.

In 1953, Cadillac sold 109,651 automobiles. Packard sold 90,252. Though that superficially suggests Packard was competitive, the raw numbers don’t tell the full story. Cadillacs were sold only in the luxury car market. Most of Packard’s sales were in the mid-price market. In that market, Packard competed against Buick with 468,755 automobiles sold in 1953 and Oldsmobile with sales of 344,462 in 1953. It also competed with Chrysler, DeSoto, and Hudson. Even Lincoln, with sales of 40,473 automobiles in 1953, outsold Packard in the luxury market.

Seen in this light, it is obvious that Packard was uncompetitive in both luxury and mid-priced ranges. That is why Nance wanted to move the Packard brand fully into the luxury market and separate its identity from that of the Clipper. The luxury market was the smaller pond, where prices and profits were higher and where, though the competition with Cadillac would be challenging, at least there were fewer brands competing.

Separating the Packard and Clipper model lines was simply the first step in a plan, initiated under Ferry but revised and accelerated by Nance, to introduce fully new models with V-8 engines. As adopted by Packard’s executive committee in November of 1952, the 1954 Packard line would receive an entirely new body. The 1954 Clipper would be a facelift. In 1955, the V-8 would be introduced, the Packard would receive a facelift, and the Clipper would be all new. As the plan’s implementation progressed, the 1954 target became 1955. It was all part of a plan Nance envisioned that spread over five years and aimed at fully reestablishing Packard in the luxury automobile field by 1958.

Cadillac, however, had established itself. If it were not the “Standard of the World” as it claimed, certainly it was the standard against which any luxury automobile would be compared. It had the best styling, the best technology, and – as Nance’s “kid at the curbstone already knew – was considered “the best.”

And Cadillac would not be standing still while Packard tried to catch up.

Moreover, even Nance’s plan did not truly change the company’s dependence on selling middle-priced models. Though it envisioned Packard as again a true competitor in the luxury market against Cadillac, the company itself would still be competing against Buick, Oldsmobile, Chrysler, and others in the middle price market. Packard’s dealers were too dependent on selling in that market for the company to become exclusively a luxury brand manufacturer.

The rescue plan ended almost before it began.

In early 1953, the Defense Department reduced the jet engine contract from $392 million to $218 million, which equated to a $42 million decrease in 1953 contract revenue.

Then Briggs fell short of production targets, by 5,000 vehicles in the first quarter of 1953.

Packard was still making an operating profit, but the supply of unsold cars was building to 55 days, as the sales of the more expensive models were declining. This compared to an industry average supply of 31 days. The backlog of unsold models meant cutting production numbers below break-even to avoid a glut. The company was still reported a profit for the year, but the drop in sales would continue into 1954, as the models introduced in 1952 entered their third year of production. Plans to begin production of the 1954 models in October were modified to begin production in January of 1954.

Then the government further cut back on the jet engine contract, reducing the rate of production but extending the duration of the production run. That again reduced annual contract income.

On January 17, 1952, Walter O. Brigg died. To pay federal estate taxes, the heirs sold the company to Chrysler Corporation, for whom Briggs had also been manufacturing bodies. That would ultimately force Packard to again produce bodies itself.

It was then, on March 1, 1954, that company treasurer Walter Grant wrote Nance that “the company is rapidly approaching bankruptcy.” “Substantial expenditures” were needed to complete the new engine plant (for the V-8) and lease the Connor Avenue body assembly plant from Briggs. (The lease was $758,568 per year for five years. Cost of setting up production was projected at $3,000,000.) At the existing rate of expense, working capital would be exhausted by June 30, 1955. An $11,000,000 pre-tax loss was expected for the year, and current inventories of unsold models at dealers and Packard inventory exceeded 90 days’ supply.

It was these circumstances that led to the decision to hire investment banking firm Lehman Brothers to evaluate combining with Studebaker. Their report unequivocally recommended doing so. The financial press, as well, encouraged the companies to join. In its August 30, 1954, issue, Time magazine summed up the prevailing view:

“For its part, Packard will get the advantages of the slick styling that has made Studebaker a pacesetter in postwar auto trends, will also get the benefits of Studebaker’s strong dealer organization around the U.S. Packard, which has long had trouble getting dealers to take on its big cars in fringe markets, will start off by doubling up with Studebaker to sell Packards in 1,000 towns too small to support a full-time Packard agency. In turn, Studebaker will profit from Packard’s solid engineering and its strong financial position.”

Packard, however, had no such “strong financial position.” It merely had cash in the bank.

Packard’s acquisition of Studebaker was completed on October 1, 1954. Studebaker’s board chairman, Paul G. Hoffman – a business luminary who had served as director of the Marshall Plan in Europe for five years before returning to Studebaker – was given the same role at Studebaker-Packard. Packard executives later maintained that Studebaker falsified information provided to Packard, including its production break-even volume. That may be so, but it is equally true that Packard’s board of directors and officers, including Nance, made no effort to have the Studebaker books independently audited before proceeding with the acquisition.

The truth is that none of that mattered. The acquisition of Studebaker was born of desperation. It was Packard’s only chance. With it, the combination might still fail. It did not matter. Packard was doomed. If it did not combine with Studebaker, Packard would be bankrupt – probably within the year.

Studebaker would post a $12 million loss for 1954, while Packard’s loss was $2 million.

James Nance did not save the Packard brand.

That was not his job. It was not what he was hired to do.

He was hired to save the company.

He did that.

Though saving the Packard brand was one way to save the company, that way would turn out to be impossible.

Yet, Nance still did his job. He did save the company.

Studebaker-Packard would struggle into the 1960’s manufacturing automobiles and incurring losses throughout, except for the few bright years in which it was able to rebody an obsolete model as the Lark and sell it to a public as an economy car. Yet, those accumulated losses allowed Studebaker to avoid income taxation as it reorganized itself into a mini conglomerate of divisions, including Onan generators, STP, Gravely commercial grade lawn mowers, Clarke floor machines, that were profitable. Ultimately, it would exit the automobile business entirely, and – now known only as Studebaker Corporation – be acquired by Worthington Corporation.

In a recent column in the British publication Octane, Jay Leno cites Packard as “a precursor to what happened to the American automobile industry.” He states, “And one of the final nails in the coffin was bringing in James Nance – a man with absolutely no experience of automobiles who came from a background in selling appliances.”

Leno’s wrong about that.

James Nance did not kill Packard. That was done by others.

He saved the company.

Continued from Part One and Part Two

See also previous posts: The Real Reason Packard Died and Pat Foster and the Myths of Packard’s Demise.